[ad_1]

As I was sorting through photographs to be featured in the second part of this series, which at this point is shaping up to be four-part strong, I was also contemplating how to accompany them with a side dish of meaningful writing. The end result is a complete 4-course meal of fluorescent greens that also try to answer the essential questions directly related to the photographic topic:

- What is coral fluorescence?

- Why do corals fluoresce?

- How does one capture fluorescence on camera?

Today is good day to start answering these questions. First: what is coral fluorescence? What is fluorescence in general?

I can start by telling you what it is not.

There are two main ways for living organisms to glow in the dark- bioluminescence and fluorescence. The fundamental difference between these two phenomena is simple- one can occur on its own within the organism, the other needs an outside source of energy to manifest itself. Let me explain.

Bioluminescence is a type of chemiluminescence, the ability of a living organism to emit its own light by a chemical reaction occurring within the organism’s tissue. That reaction differs from animal to animal or fungi to fungi (as bioluminescence is almost entirely exclusive to animals and fungi, with the exemption of Dinoflagellates that, let’s be honest, are plant-like at most), but the end effect is similar- the organism glows and gives out enough light to illuminate its surrounding. Fireflies are the best and most recognizable type of animal that we associate with bioluminescence, but the list of species that have this fascinating ability is wide across the Animalia branch of the tree of life- glowworms and bioluminescent caterpillars, but mostly marine animals such as bacteria, tunicates, squid, deepwater fish, and various invertebrates. In fact, over 75% of all known deepwater animal species have some form of bioluminescence mechanism they use for various reasons, like communication, defense purposes, or to lure unexpecting prey, as the anglerfishes do.

A simple explanation says that fluorescence is [direct Wikipedia quote]:

“…the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation.”

Or in other words, the substance in question absorbs light of one wavelength and emits it back in another wavelength, almost always one of lower energy due to some energy lost as heat.

Fluorescence has little in common with bioluminescence. First of all, it is not restricted to living things- some minerals fluoresce, for example. But we reef aquarists think of fluorescence in terms of the corals and other sessile invertebrates we keep in our tanks. Corals exhibit the most eye-pleasing form of fluorescence, where high energy light from outside (or almost outside) the visible spectrum (UV or near UV) is re-emitted as visible light.

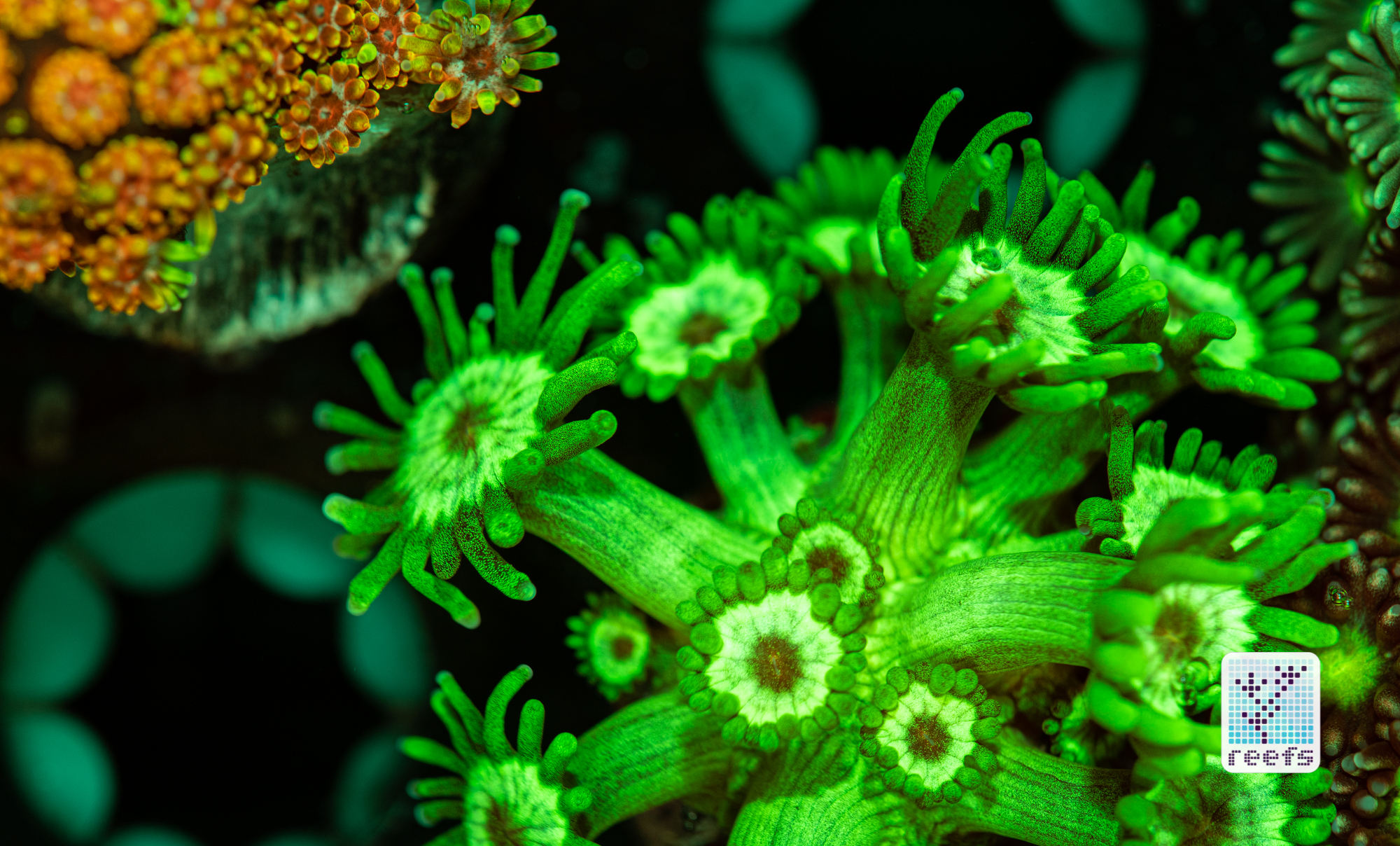

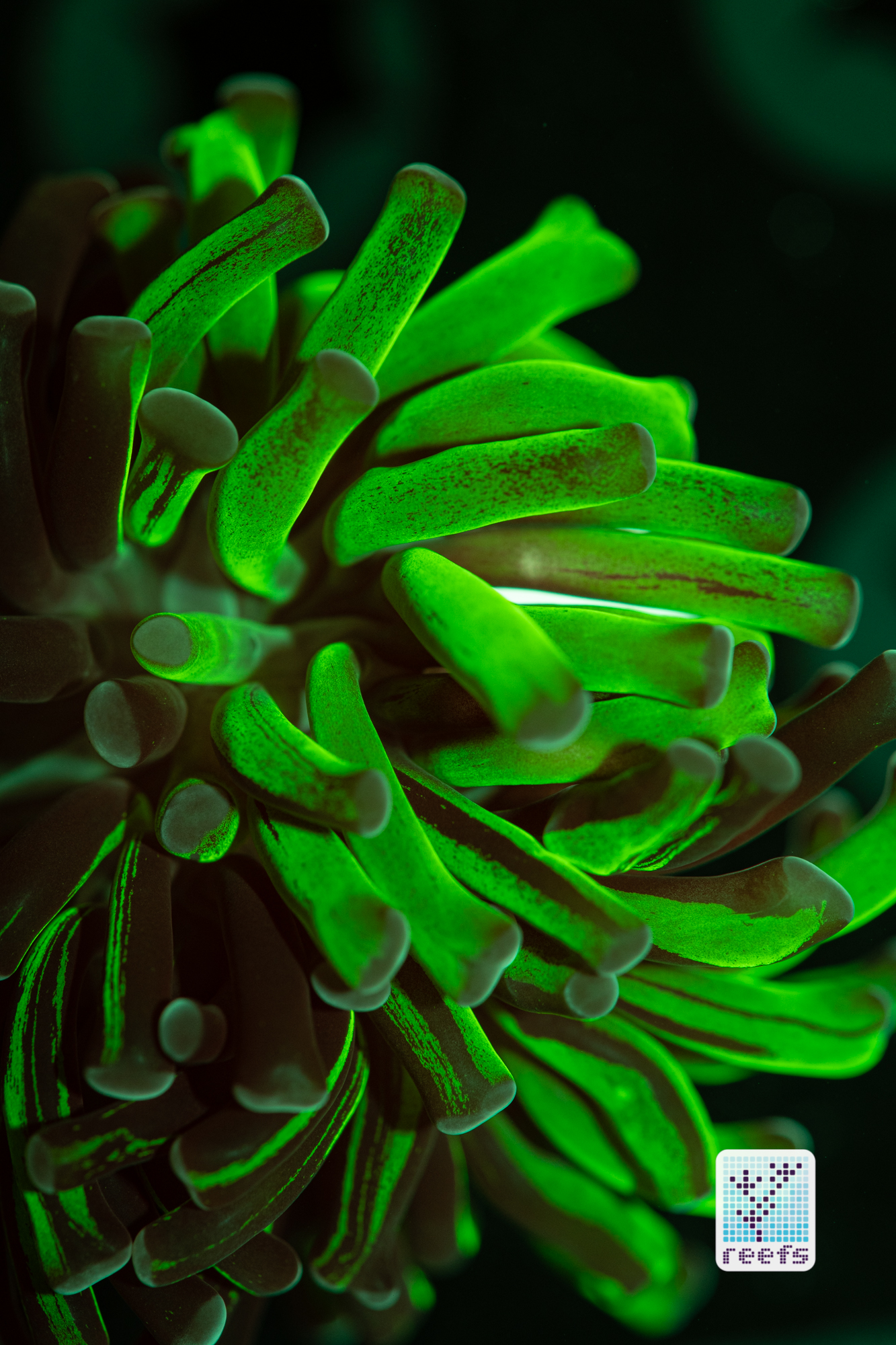

Fluorescence is a temporary show and to reenact it, one needs a source of UV or near-UV light to see the color change phenomena in its full glory. What a show it is though! Fluorescence in corals is spectacular, even more so than any other aspect corals posses. It occurs in various glowing shades of green, yellow, and red, at different concentrations and in different parts of the animals. When they glow, every single polyp has its own pattern that identifies it, almost like an underwater fingerprint.

It’s a truly amazing natural occurrence and my absolute favorite thing about corals. However, as with everything nature does, fluorescence is not only there to please our eyes- it serves a purpose. What’s that purpose?

Stay tuned for Part Three to find the answ… well, the most current explanation based on the best knowledge…

[ad_2]

Source link