[ad_1]

Mushroom Corals or Corallimorphs are great beginner corals because they are some of the easiest species to care for. I recommend mushroom corals for hobbyists at any level. They are hardy, tolerant of some less than ideal reef tank parameters or conditions, will grow in areas of lower light, and can be easily fragged or will reproduce on their own.

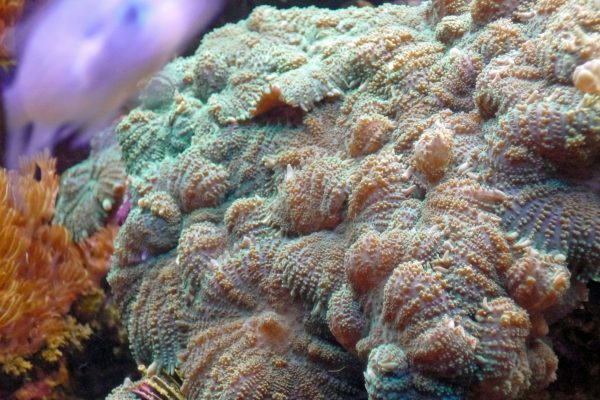

This mushroom coral colony was one of my first corals every purchased

Mushroom coral care quick facts

- Common names: Mushroom coral, Mushroom anemones, Bounce coral, False coral, Ricordea

- Scientific names: Corallimorpharia, Actinodiscus, Discosoma, Rhodactis, Ricordea

- Care level: Most species are easy, a few of the more rare mushrooms require moderate care

- Light level: Most require low to moderate light intensity/quality, a few of the brightest color varieties do need higher intensity light

- Flow level: Most require low to moderate water flow

- Aggression: Mostly Peaceful. No stinging sweeper tentacles, but it will try to outgrow and grow over any nearby corals.

Natural habitat

Mushroom corals are generally found in lower light, nutrient-rich environments, which makes them somewhat ideal inhabitants in a mixed species tank including fish and coral, and easier to care for than some of the most finicky coral species. They have symbiotic photosynthetic zooxanthellae and require low to moderate light, are not picky about flow, and can be kept in less than pristine conditions.

What’s in a name (Taxonomy and common name confusion)?

All Mushroom corals are Corallimoprharians, which is the taxonomic ORDER they belong to (Corallimorpharia). As you get deeper into the taxonomic classifications, there are several different families, genera, and species. It’s interesting to see the range of common names used to describe this fascinating group of animals: False corals, Disc corals, and Mushroom anemones are three common names that generally seem to describe them. But being mushroom-shaped or disc-shaped feel like two completely different growth forms–why are these seemingly different descriptions? Now that you mention it, they do look a bit like tiny carpet anemones…so…are these False corals really anemones?

If you want to start a fight in a room of taxonomists, bring this up.

Mushroom anemones or Disc anemones

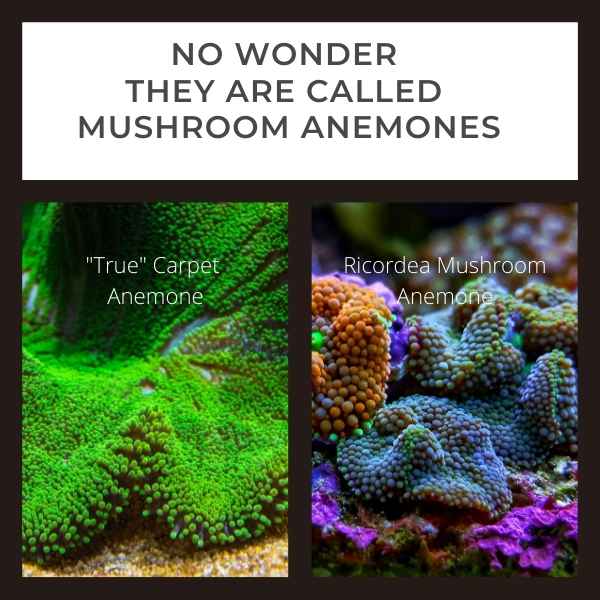

Take a look at the image below and you can see how they have earned the common name mushroom anemones. Many of them do, in fact, look a lot like anemones.

On the left is an image of a “True” Carpet Anemone and on the right is a group of Ricordea

False corals

Unlike other corals, Mushroom corals don’t have a skeleton. Even true soft corals have the remnants of skeletons, called sclerites, which are tiny bone shards/slivers embedded in their tissue. But Mushroom corals do not, hence the justification for calling them False corals.

They also don’t have long, retractable feeding tentacles to capture prey (Borneman 2004). These are at least two of the reasons they have earned the common name, False corals.

Mushroom corals

In lower light environments, the individual polyps from any species of mushroom corals will stretch upward in the water column, creating a mushroom-like appearance.

Amazing to see them stretch towards the light like this–this growth form and behavior is not unique to a particular species, but rather characteristic of the entire group under lower lighting conditions

Disc corals

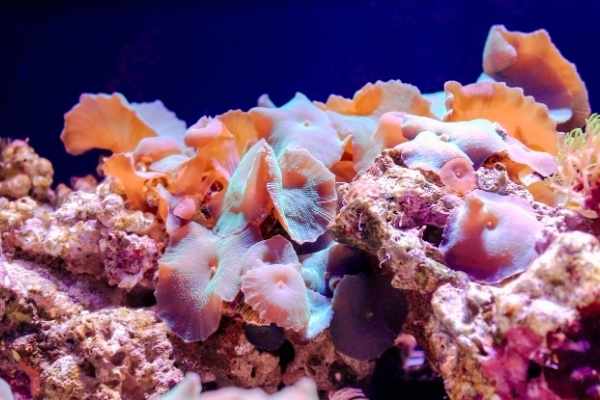

In normal-to-higher light environments, the polyps lie flat along the substrate and take on a discoid shape.

Red Actinodiscus mushrooms

Mushroom coral types (families)

There are three popular families of Mushroom corals available in the Aquarium trade.

Rhodactis

The Rhodactis mushrooms can be identified by the fuzzy or texture on the disc cap

Note the fuzzy or ‘hairy’ texture classically associated with Rhodactis mushrooms

Actinodiscus

The Actinodiscus mushrooms sometimes have a bumpy texture or stripes, but they also somehow look smoother/shinier than either Rhodactis or Ricordea

Actinodiscus

Ricordea

Ricordea, by comparison, are generally distinguished by a more uniform, bulbous appearance

The bulbous texture of the Ricordea mushrooms

What do mushroom corals eat?

Many mushroom corals will get a significant amount of their nutrition from their symbiotic zooxanthellae, which are small photosynthetic sugar daddy’s (almost literally). They will also absorb nutrients from the water. Each polyp also does have a mouth and is capable of ingesting small meaty foods, as well. Larger species, like the elephant ear, can be fed meaty foods just like an anemone.

Can mushroom corals move?

Yes, mushroom corals can move and probably will move about your tank, to the location they prefer the most. Resistance, on the part of the aquarium-owner, is generally futile. I have had mushrooms move from back to front, front to back, side-to-side, everywhere except where they are supposed to be, even to the point where they vanished, only to be seen again, in a completely new place, a few months later.

How do mushroom corals reproduce?

Like most other corals, mushroom corals are able to reproduce sexually and asexually. Sexual reproduction involves the release of gametes into the water (eggs and sperm). Fertilized eggs become embryos and the corals then settle, with half of their genetic information from mom and pop. This occurs normally on ocean reefs but is rare in the home aquarium.

The more common reproductive method in the reef tank is asexual fragmentation through either budding, splitting, both of which are natural and performed by the coral itself, or active fragging by the tank owner.

Budding

Budding is a process where the coral extends a small portion of their foot or stalk out beyond where the rest of the base is located. It then attaches to the rock further away from the base and then detaches from the original base, leaving that little piece of its foot out in front. That tiny piece of the foot then starts to transform into a fully formed, genetically identical mushroom coral clone.

Splitting

Splitting is a process where the corallimorph actually forms a second mouth and bifurcates down the center, essentially cutting itself in half—while each half re-grows to full size. It looks a little like cell division, in slow motion. The two halves will space themselves out, once completely split–and just like in budding, the two split halves are genetically identical.

Eventually, the lobes of this large mushroom cap will pinch completely and split into two separate colonies

Fragging

Technically, the word fragmentation or fragging could apply to any of these methods of asexual reproduction by breaking off a tiny piece of the parent, including budding and splitting, as described above. But in the context of this hobby, the word is generally used to refer to the process a human takes to actively exploit (not in a bad way) this amazing natural ability to create tiny clones of their corals, for the purposes of aquascaping and filling out their tanks with more corals or to trade to the local fish store or to other hobbyists.

How to frag a mushroom coral

At its most basic level, fragging any coral involves the following steps:

- Cutting or breaking off a piece of the coral from the parent/original colony

- Attaching that piece to a frag plug, piece of live rock rubble, shell, or another substrate

Where it can become a little bit more complicated is when you factor in the individual needs and challenges of the corals involved. For example, one of the positive factors that make life easier, when fragging a mushroom coral vs. a plate coral, for example, is that any frag or piece of the Corallimorph that you slice away from the original is capable of forming an entirely new colony. Larger pieces will form larger frags, but all you have to do is manage to slice of any piece and you should be fine.

The trickiest aspects in learning how to frag a mushroom coral are:

- How to cleanly/easily free the sliced piece from the live rock

- How to attach the new fragment to your preferred substrate

Freeing your frag from the live rock

Remember, the mushroom coral is attached to the live rock by a tiny foot and stalk. The easiest ways to make a frag are either to:

- Slice off the entire cap, with a horizontal slice, leaving the foot and stalk behind, if you can easily get under the cap to make the cut, or

- Slice down to cut off a large lobe, using an angle that cuts away from the food.

It is worth repeating–you can cut just about any piece of the mushroom off to create a frag. The reason I advocate for one of the two angles above is that the foot can sometimes be really well attached to tiny crevices in the live rock. I have had some challenges, in the past, removing my frag, once sliced, if my frag had too much of the foot attached to an irregular, natural surface.

Attaching it to a substrate

The next challenge in how to frag mushroom coral is figuring out how to attach your new slice of shroom to your coral plug or rubble. Mushroom corals are notoriously slimy escape artists. My preferred method is to put a bunch of rubble or plugs in a small plastic container (the kind you would save food in), place the frags inside, and cover it with a plastic mesh (from fruit, onions, or bridal veil), and then place that container in an area of low flow for about a week.

The fragments will settle and attach to the rubble in the container. Once they do that, you can remove them and attach them where you want them.

Learn more about how to frag mushroom corals and other corals

There are two places I strongly recommend to learn more about how to frag corals:

- Check out this series of articles that starts with: Introduction to fragging corals

- Download this definitive guide on Amazon, book 4 in the Reef Aquarium Book Series

A few final care tips

- If you plan to keep these corals with smaller saltwater fish, avoid large mushroom species like the ‘Elephant Ear’ or ‘giant cup mushroom’, which will snack on unsuspecting smaller fish who get too close.

- Not all Mushroom species are for beginners. If you consider yourself an intermediate or advanced aquarist and want to add a more challenging mushroom to your tank, consider adding a mushroom from the Genus Ricordea.

- The two most popular species in the aquarium hobby are Ricordea florida and Ricordea yuma. These species require more pristine conditions and generally have a higher light requirement.

What to read next

Learn more about some of the other popular types of corals:

References:

Borneman, Eric H. Aquarium Corals. T.F.H. Publications. New Jersey 2004.

Ulrich III, Albert B. How to Frag Corals. www.SaltwaterAquariumBlog.com Publications 2015

Ulrich III, Albert B. The New Saltwater Aquarium Guide. www.SaltwaterAquariumBlog.com Publications 2014.

[ad_2]

Source link