[ad_1]

The term soft coral is used broadly and relatively unscientifically (is that even a word?) to lump a bunch of related and unrelated coral species into a simple bucket, defined primarily by what they are (soft, with the absence of a major stony external skeleton) and what they are not (they are not mushrooms or zoanthids).

The reason any of this is important and worth reading about is that many of these amazing animals (yes, they are animals), are some of the most popular, readily available and easiest to care for aquarium corals you will find in this hobby.

What you will find in this article

What is the difference between hard and soft coral?

Hard corals, like LPS and SPS (which stands for Large Polyp Stony and Small Polyp Stony), have a substantial external skeleton made of calcium carbonate.

Soft corals, by comparison, have very large, soft, fleshy polyps with tiny pieces of calcium carbonate skeleton included into their tissue. These tiny pieces of the skeleton, called sclerites, look like little crescent moons or even fingernail clippings (gross!).

If you look closely, you can sometimes see these sclerites embedded in the tissue of certain corals.

Unlike zoanthids and mushroom corals, these are considered to be “true” corals and not colonial anemones or false corals. That doesn’t really mean all that much for the average hobbyist other than to provide some specificity about what we mean when we use the term soft corals.

What makes a true soft coral species?

The true soft corals belong to the octocorillian family, which is a term used to describe the corals that are radially symmetrical divisible by 8….er…what? Ok, picture an old school clock with numbers from 1-12…roughly speaking that’s radially symmetrical as divided by 12…now imagine that clock only had hours 1-8, evenly spaced around the clock.

Zoanthids, by comparison, are hexacorals and have a different body structure than the true soft corals. The most common soft corals in the hobby are part of the Alcyoniidae family…which is the same thing as saying they are leather corals.

The polyps of octocorillians have 8 tentacles. Go ahead, count them.

Here are some of the most popular soft corals available in the hobby:

This is not an exhaustive list, but these are the ones you are most likely going to find in a store.

Don’t be allured by this beauty, they are hard to care for

Care

It is a bit tricky (or imprecise) to try and provide care instructions for a grouping of corals as large and diverse as soft corals. But what I will do here is try to focus on the most commonly available varieties.

Soft corals are so popular because many of the species are considered beginner corals. What makes a beginner coral? They are hardy, which means they grow well, they are tolerant of aquarium conditions, perhaps a bit forgiving of minor fluctuations in water quality and only require a moderate amount of light and water flow.

That pretty much describes the cabbage leather, toadstool, devil’s hand, finger leathers, pulsing xenia, Capella, colt corals, and other similar corals. Standard reef aquarium water parameters will grow these corals well.

How to grow soft coral faster

The key to boosting the growth of your soft coral is to (gradually) increase the quality of light (meaning give it more PAR or a higher value of PAR) and to feed your tank a few times a week.

I’ve fed my tanks with rotifers,

phytoplankton and baby brine shrimp, to make a variety of food sizes available.

Testing

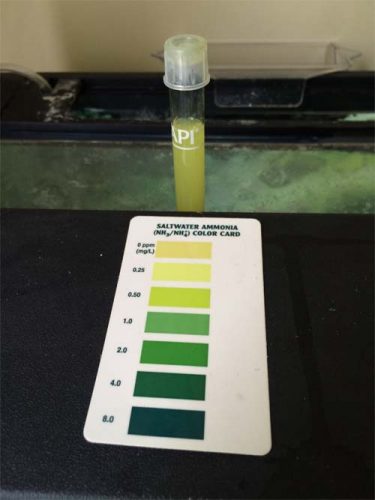

You shouldn’t have too many problems keeping water parameters around these levels, as long as you use a high-quality salt mix.

Dosing

Feeding

Corals are animals. Animals like to eat. In addition to providing a good source of reef-building aquarium light, you may also want to feed your corals.

While there is a common belief that soft corals do not require food, that is actually a myth and is quite untrue (Borneman 2001).

While the polyps of your average soft coral species might not have stinging nematocysts, or even the same dramatically visible capture-response that you might see in some other SPS coral species, that doesn’t mean they don’t eat.

Cabbage leather corals and some others have polyps that are capable of capturing and ingesting prey. If the corals you have capture prey, it’s typically a good thing to feed them. A stand-out exception to this rule is with the non-photosynthetic soft corals, like the carnation, which is actually incapable of sustaining itself with photosynthesis.

These corals require regular feeding to survive and are actually not recommended for the beginner aquarist.

The key to feeding any coral species, whether soft or hard, is to provide it with food that is the right particle size. Many soft coral species will absorb nutrients right from the water, and others may feed on nanoplankton or bacterioplankton.

If the feeding habits of the coral you’re interested in are not well described, I encourage you to try different feeding regimens and share your results (here or with others).

Fragging

Fragging soft corals is a fairly straightforward exercise. You want to cut off a piece and attach it to a piece of live rock or a frag plug. If you are trying to frag one of the encrusting species (like green star polyps), creating soft coral frags is even easier, because the GSP will just encrust any adjacent rock in reach. All you will need to do is separate the new rock colony from the parent.

Cutting soft corals is easy, you just use a razor blade or a sharp set of scissors.

How to attach to live rock

Attaching soft corals can be challenging because they typically are not able to be glued into place.

Since many of these soft fleshy polyps are escape artists of the aquarium world, you can use any of the following methods to attach them to live rock (or a plug):

- Plastic container and mesh

- Rubber band

- Toothpick method

to attach them. You can find step-by-step instructions for all of these in the book, How to Frag Corals (there is a link for that below if you are interested in reading more…and thank you!). I also wrote more about the topic here.

Where to buy

The best value for the money can usually be found by buying frags from a fellow hobbyist in your area. Many of the soft coral species commonly kept in the hobby can be fragged easily. So your best bet at getting a hardy, inexpensive specimen that is used to life in an aquarium is to get a piece that is doing well in someone else’s aquarium.

After that, the next best option is to get an aquacultured specimen online or at your local fish store. The term “aquacultured” means that the coral was grown (farmed) in captivity and is also likely to adjust better to aquarium conditions in your home than a wild-caught one.

Best varieties for beginners

The 3 best saltwater coral species for beginners are:

- Green star polyps (this soft coral looks like grass)

- Toadstool

- Kenya tree (also called colt)

I have kept those three more than any other coral type, over the years, because they’re awesome, easy to care for and easy to propagate.

[ad_2]

Source link