[ad_1]

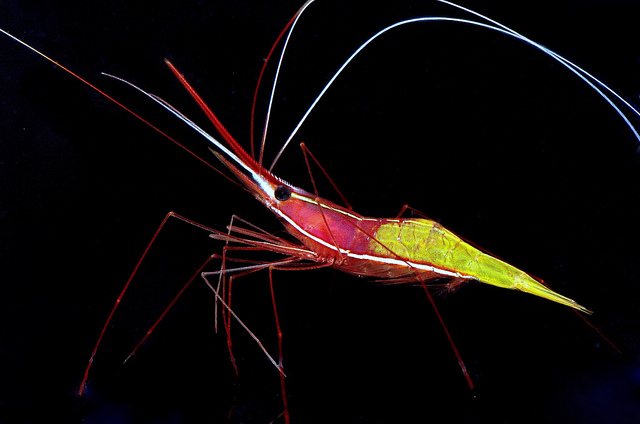

Plesionika flavicauda, Coral Sea. An aquarium specimen at Cairns Marine. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

The genus Plesionika strikes a stunning chord of paradoxical dichotomy in the world of invertebrates. For one, this genus comprises well over a hundred species, widely distributed throughout the Pacific Ocean – from the reefs of the Indo-Pacific, to far east in the French Polynesia. Yet, it remains as one of the most poorly studied and documented genus of shrimps, with undoubtedly many more species awaiting discovery, and many more existing species awaiting rediscovery. These delicate, elegant crustaceans with spindly legs and wispy antennae are often ornately patterned, frequenting ledges and caves in deep waters. There, they occur in groups ranging anywhere from a dozen individuals, to seemingly endless hordes. More often than not, these marauding plagues travel in an almost fluid like manner, indiscernible in the murky darkness, sans the filamentous conglomeration of antennae and moving legs.

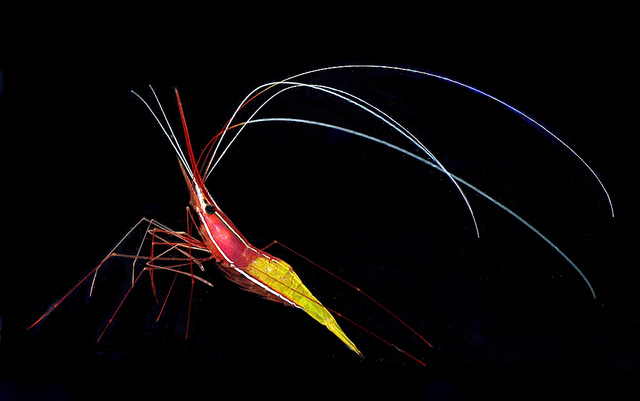

Plesionika flavicauda. Shrimps in this genus can attain commendable sizes. Here, a specimen stands stoic and resolute at 12 centimetres. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

One particular species stands out, not only for its breathtaking beauty, but also for its behavioural quirks unknown to science. Plesionika flavicauda is a deepwater species found primarily in the tropical reefs of Oceania. In this species, the carapace and the anterior abdominal segments are deep maraschino. The posterior abdominal segments are highlighter chartreuse, spreading to the tail and telson. A pair of white lines run parallel along the dorsomedian ridge and lower part of the abdomen respectively. It is quite likely that this species is represented by various geographical crypts throughout its range, but too little is known to draw any actual conclusions with regards to its biogeography.

A young Cephalopholis igarashiensis in captivity. This species is extremely rare in the trade. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

Unlike most Plesionika spp, P. flavicauda is always documented in the presence of the grouper species Cephalopholis igarashiensis, otherwise known as the neptune Grouper. This unusual pairing is quite perplexing, for it’s not often you’d find a predatory fish in the company of its prey. Yet this happens to occur quite frequently, and in multiple dives conducted by Dr. Richard Pyle and Brian Greene, the grouper was never once observed without the company of P. flavicauda. It could be argued, however, that this is simplly a case of serendipitous coincidence; after all, both animals frequent the same depth range and niche habitats.

Plesionika flavicauda in the company of Cephalopholis igarashiensis in 64m, Marquesas. Photo credit: AAMP.

Strangely enough, no other species of Plesionika have been observed to exhibit specific pairings with any particular piscine. What evolutionary benefit could this pairing, if it were to so occur, possibly offer? Are the shrimps facultative cleaners for these deepwater grouper species? Could they possibly be favourite prey items for C. igarashiensis? No one really knows, and the sampling data size of these documented occurrences are not quite extensive enough to draw any conclusions. The photo and video above demonstrates this oddity pretty well in the mesophotic reefs of the Marquesas and Pohnpei.

Regardless, it is a unique and interesting pairing of a somewhat unorthodox nature. Even the similarities in color combination raises some red flags. Perhaps this relationship could be one day elucidated with extensive deepwater submersible explorations and rebreather dive surveys. On another note, the video above shows P. narval in a writhing swarm of seemingly endless individuals, meandering about the seascape like an underwater river. This behavior is not uncommon, especially in this species. Pay attention to the lurking grouper as it takes advantage of the camera’s light, illuminating its surrounding just quick enough for a snack.

[ad_2]

Source link